Art in the Civic Space

This Grief Thing, 2021: Photograph: Method Studios

If we removed culture, what would our cities, towns and villages be? What do we want our places and spaces to say about our values? How do we create a public realm that includes us all? Creativity in the public realm is an essential part of our interaction with place and with each other. Artists are a vital part of the jigsaw of inter-connected spaces, essential to the life blood of place and to providing creative experiences to communities.

The arts are irrepressible and have always worked through complex problems with imagination and nuance. The current crises in the cultural, social, housing, education and health sectors are deeply connected and our response must be collaborative, imaginative and radical. It is a herculean task to address chronic underfunding and requires considerable adaptability and creative thinking.

Artists and arts and cultural organisations face very real threats to survival. The legacy of Covid; the consequences of Brexit; the cost of living crisis; systemic misogyny, racism and ableism; social immobility; the climate & refugee emergencies; the assault on statutory funding - the challenges feel overwhelming. The cultural sector is facing more challenges of funding, sustainability, workforce retention, capacity, resourcing and livelihood precarity than ever before.

This Grief Thing, Middlesbrough, 2018. Photograph: Sam Butler and David Harradine

As small and large arts organisations and statutory services alike face these challenges, and very real threats to their survival, the public realm becomes the gallery, the performance space and music venue of, by and for the people. Art in our civic spaces brings culture within reach of everyone, responding to and enhancing people’s day-to-day experience. The urgency is to embed creativity in public spaces with ambition and purpose, benefitting physical, emotional and mental health, connecting and inspiring future generations. The argument for arts and culture seems weak against the more tangible threat of global strife and the breakdown of basic services. But if we remove culture, what does that say about what and whom we prioritise? Empathy and connection are needed more than ever. We all deserve a culture of excellence - one that offers experiences that are exhilarating, thought provoking, challenging, comforting, enthralling and which offer hope and joy.

Collectively, we need to fund and create work that thinks creatively about the interplay of sectors, to animate virtual and physical multi-functional spaces, explore how we authentically meet people where they are. How will we emerge from the chronic effects of austerity? Art in the civic space creates opportunities and connections for radical social practice and engagement, as a conduit between the public realm, lived experience and public health.

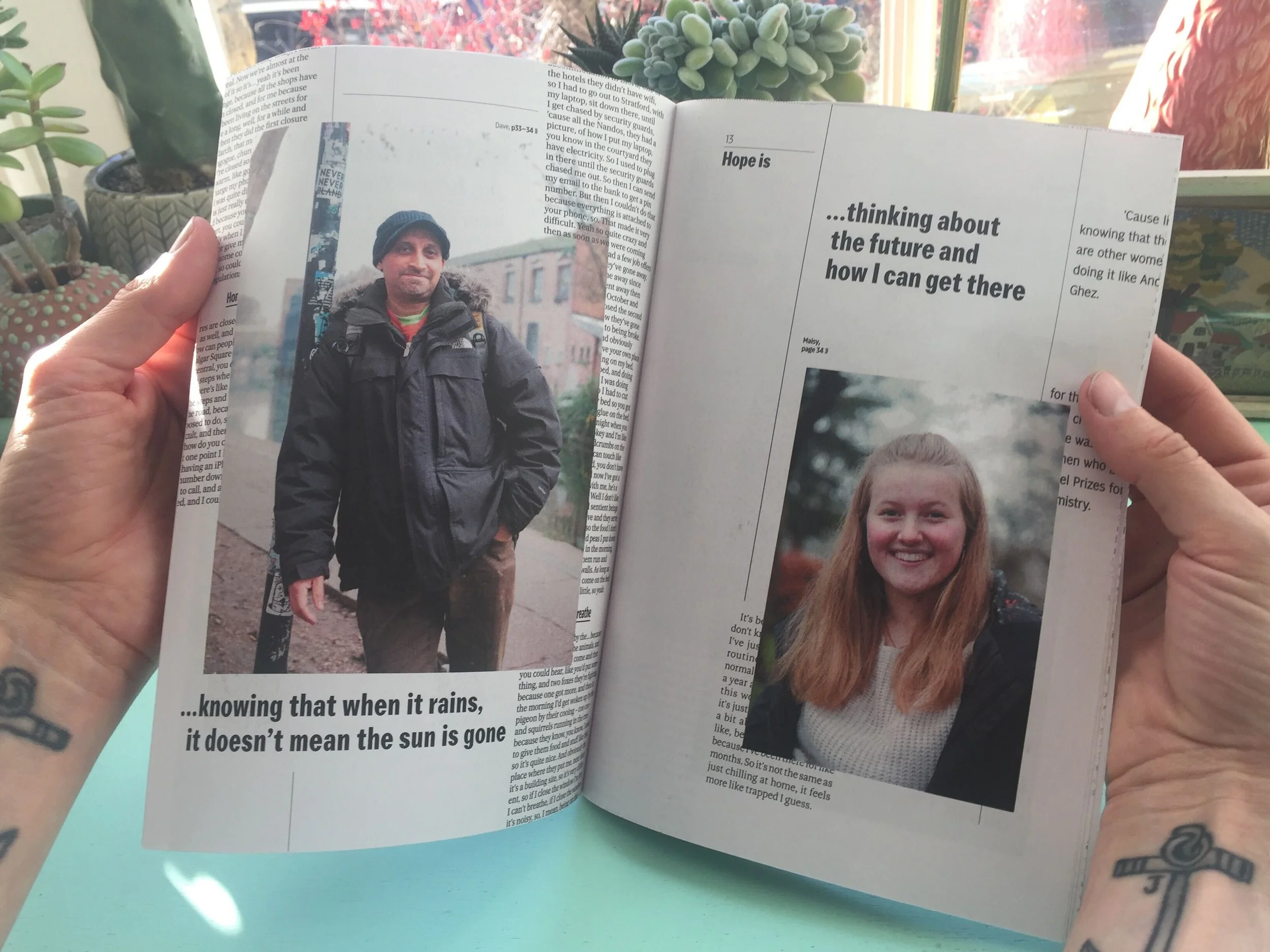

Hope Is… Newspaper, 2021. Photograph David Harradine.

Hope Is… poster campaign, 2021. Photograph: Paul Akinrinlola

Children’s Day, Leeds, 2024. Photograph: David Harradine

I feel deep sadness, frustration and anger that artists, cultural organisations and creative communities are under constant threat. Moving artists and the creative programmes that they generate and deliver to the literal and figurative margins diminishes the places and spaces in which we connect, live, study, work, and generally rub along together. The future of social need requires urgent action in how we build, occupy and programme systems, and physical and virtual spaces. The nature of the skills, collaborations and resources required mean that artists and other civic roles will increasingly need each other. Artists bring imagination, a cultural economy and a creative diversity that go far beyond homogenised town centres and high streets. Art is the mortar that joins essential provision with the human experience. Art is a public service.

Neon light installation by artist Martin Creed. Photograph: Jane Barlow/PA

Reaching Out by artist Thomas J Price at Three Mills Green, near Stratford. Photograph: Linda Nylind/The Guardian